4-minute read

Premise

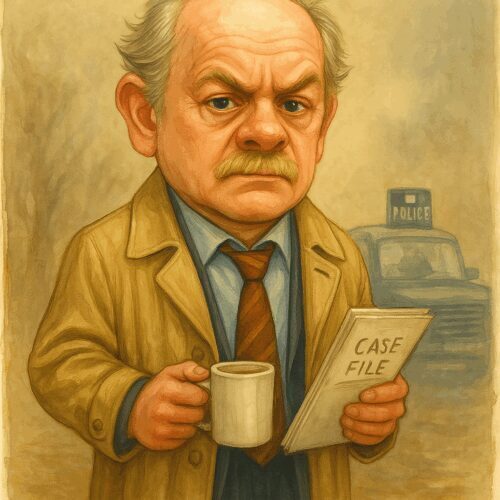

Remember those long nights watching British telly, hooked on a crime show that took its time? That’s A Touch of Frost. Picture a grumpy detective with a dry wit, cracking cases in damp Yorkshire towns. You kept watching because Frost’s unorthodox methods and moral gray areas felt real. Plus, the pacing was slow enough to savor every characters’ bloody quirks, but intense enough to keep you glued. It’s the sort of series where the gloomy opening theme and gritty visuals made you want to settle in for an understanding of what really lies beneath the surface of society.

Characters

- DI Jack Frost: The grumpy genius, famous for his sardonic humor, a soft heart hidden under a disheveled exterior. He’s always on the edge, fighting bureaucracy and his own personal demons.

- Superintendent Mullett: Frost’s boss, a stiff-upper-lip careerist who’d say “stick to protocol,” even when Frost’s instincts prove right.

- Sergeant George Toolan: Frost’s loyal sidekick. Always there, usually rolling his eyes at Frost’s antics but ready to back him up.

- Ernie Trigg: The station’s comic relief — reliable, friendly, and just a little bit daft, providing some light in the gloom.

Cultural Impact

The show made a big splash in British homes. Its down-to-earth depiction of policing and the gritty Yorkshire backdrop hit a nerve. Memes? Plenty of Frost’s deadpan line delivery became internet gold. People loved quoting his sharp comebacks and pondering his moral dilemmas. It’s one of those series that, years later, people still mention in pubs and online threads. It didn’t just entertain; it became a staple of British crime TV and a go-to reference for detective grit.

Legacy

Years on, A Touch of Frost still influences British crime dramas. It set a standard for mixing moral ambiguity with character depth. Viewers remember Sir David Jason’s Frost as the iconic face of detective work—flawed, relatable, endlessly human. Today, it’s still regarded as one of the best British cop shows, praised for steady storytelling rather than flash or sensationalism.

If You Only Watch One Episode…

Go for “Care and Protection” from 1992. It’s the pilot and basically the blueprint. Frost investigates the kidnapping of a child while managing grief after his own wife’s death. It introduces his unorthodox style and sets the tone for the series. Plus, it’s packed with the quiet intensity and moral complexity that made the show a classic. Watching this episode gives you the whole vibe—gritty, thoughtful, with Frost’s witty lines quietly cutting through the gloom.