4-minute read

Premise

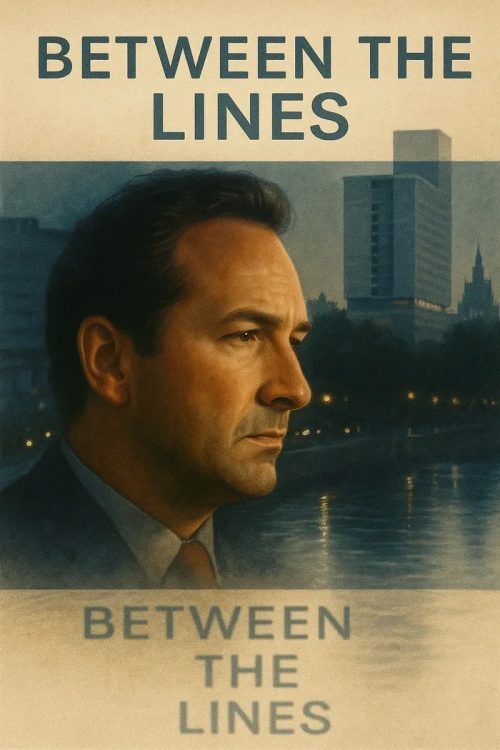

If you were around in the early ’90s, chances are you kept watching Between the Lines because it was smarter and darker than most cop shows. Think gritty London streets, complex moral dilemmas, and a plot that actually made you think. It’s not your typical crime drama. The pacing is tight, with opening music that hooks you instantly. Yes, you’ll binge just to find out who’s dirty and who’s clean. It kept viewers glued, eager to unravel a web of corruption and political intrigue. The show pulls no punches, making you question the very fabric of law enforcement.

Characters

- Detective Superintendent Tony Clark – Played by Neil Pearson. He’s the ethical anchor in a sea of moral grey. Clark’s principled but flawed. His personal struggles mirror the corruption he fights against.

- Harry Naylor – Tom Georgeson’s tough, cynical sidekick. Always questioning authority, Naylor keeps Clark grounded and adds a pinch of dry wit.

- Detective Inspector Maureen Connell – Siobhan Redmond’s sharp and loyal cop. She’s the moral compass, often torn between the duty and her loyalty to Clark.

- Angela Berridge – Francesca Annis’ political figure. Her involvement thickens the plot and adds layers of systemic power plays.

Production and Style

Concept & Visual Aesthetic

This series feels real. It’s shot in London, using actual locations that make you feel like you’re on the street. The muted lighting and grim urban landscapes reflect the harsh realities of police work that it portrays with gritty authenticity.

Music & Tone

The soundtrack is understated but effective, heightening tension just when you think it’s safe to breathe. Every scene feels tense, driven by character conflicts and moral gray areas.

Writing & Direction

Created by J.C. Wilsher, the show avoids cliché police procedural traps. Instead, it digs into character depth, systemic failings, and the blurred lines of right and wrong. The scripts are sharp, the dialogue punchy, and the storytelling layered.

Series Structure & Major Storylines

- Series 1 (1992): Kicks off with Clark’s mission to expose police corruption. Establishes key players and tensions.

- Series 2 (1993): Deepens the corruption web. Includes organized crime and political interference. Things get darker.

- Series 3 (1994): Now it’s national security and espionage. Betrayals surface. The danger is bigger and closer to home.

Reception and Awards

- Critics loved it for sharp scripts and strong performances. It’s like a police drama meets political thriller.

- Neil Pearson’s portrayal of Clark was praised for vulnerability and grit. It’s his layered performance that made Clark truly memorable.

- It scooped a BAFTA in 1994 for Best Drama, cementing its reputation as a top-tier series.

Influence and Legacy

- It set the gold standard for British police dramas. Shows like Line of Duty and Bodyguard owe a debt to its realism.

- Fans still talk about its authentic characters and moral complexities. It’s considered a classic of the genre.

- People often cite it as one of the most important British dramas of the ’90s—a rare blend of police procedural, political intrigue, and psychology.

Iconic Episodes

- Series 1, Episode 1: Sets the tone with Clark stepping into the murky world of police corruption. It’s where the moral chess game begins.

- Series 2, Finale: Shocking revelations shake everything up. Corruption hits the highest levels, making Clark question everything.

- Series 3, Finale: A tense showdown involving espionage and betrayal. It’s a gripping conclusion that leaves you pondering loyalty and justice.

Final Thoughts

Between the Lines remains a masterclass in British crime drama. It’s tense, intelligent, and morally complex. Its performances and storytelling still hold up. If you want a series that challenges your views on police ethics and power, this is it. It’s not just entertainment; it’s a reflection of systemic flaws and human dilemmas. Still relevant today, it’s a show worth revisiting.