3-minute read

Premise

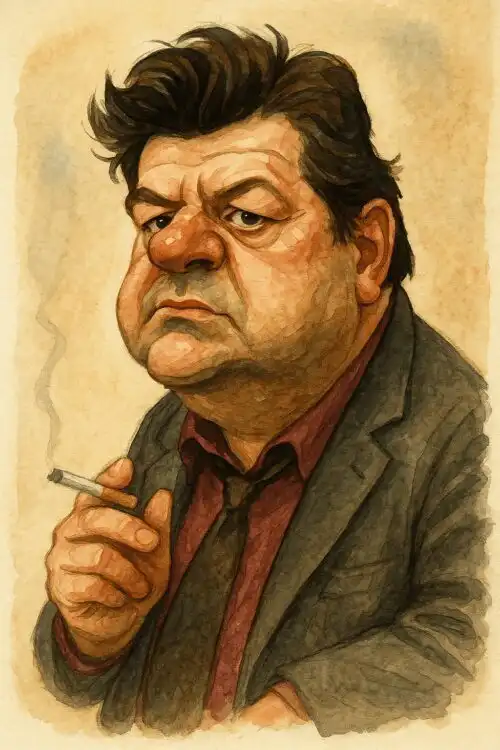

If you’re a Brit who grew up in the ‘90s, chances are you remember flicking through late-night telly and stumbling on Cracker. This gritty crime drama hooks viewers with its dark, atmospheric tone and unflinching look at human flaws. And honestly? You kept watching because Robbie Coltrane’s Fitz isn’t your typical detective—he’s chaotic, flawed, yet brilliant. That paradox pulls you in. The show’s pacing, haunting music, and nerve-wracking cases keep you glued, waiting to see how Fitz’s mess of a life and mind will unravel next.

Characters

- Dr. Edward “Fitz” Fitzgerald – The overweight, chain-smoking shrink with a knack for cracking psyche and crime. His insight is matched only by his personal chaos.

- Judith Fitzgerald – Fitz’s long-suffering wife, forever battling his addictions and infidelities. She’s the stabilizer in his stormy world.

- DCI David Bilborough – The dedicated detective, slightly conflicted, who forms a tense alliance with Fitz.

- DS Jane Penhaligon – A sharp, ambitious cop with her own trauma and fights against the sexist system.

- DCI Charlie Wise – The steady presence on the force, often serving as Fitz’s foil—calm versus chaos.

Cultural Impact

Cracker wasn’t just another police procedural. It made viewers think. People loved dissecting Fitz’s twisted psyche, quoting clever line after line. It became a meme machine, with quotable moments and clips circulating online. Its raw, unfiltered portrayal of Britain in the ‘90s carved out a special place in TV history. Broadcasters saw its power and the series set a new standard for gritty, character-driven crime dramas.

Legacy

This show changed the game. Cracker set a new bar for psychological depth in crime series. Its influence ripples through shows like Luther and Prime Suspect. Robbie Coltrane’s Fitz remains iconic. The series is still quoted, still discussed, and still revered for tackling dark, uncomfortable truths with intelligence and style. It’s a reminder that TV can be gritty and human, all at once.

If You Only Watch One Episode….

Go for “Brotherly Love” from season 2. It’s a tight, intense look at institutional corruption, homophobia, and Fitz’s moral core clashing with societal decay. This episode is a microcosm of the series’ themes—blunt, powerful, and brutally honest. Watching it gives you the perfect snapshot of what made Cracker so groundbreaking.