4-minute read

Prime Suspect: The Crime Drama That Changed Everything

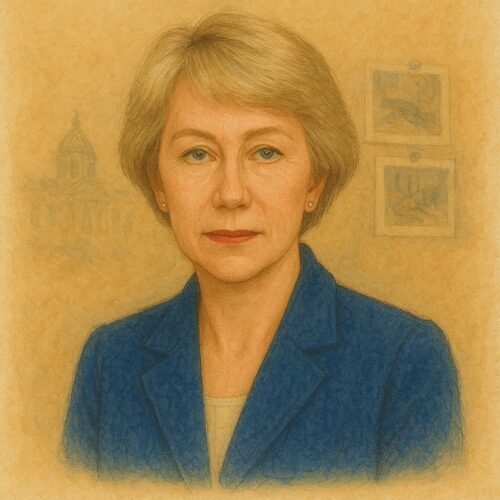

Remember those early mornings watching Prime Suspect? You just couldn’t stop. Helen Mirren’s fierce portrayal of DCI Jane Tennison kept us hooked episode after episode. Sharp dialogue, grittiness, and a heroine facing down sexism made it addictive. Plus, that haunting theme music and brooding London streets set the tone perfectly. It’s not just a crime show — it’s a gritty character study that sticks with you.

Premise from a Gen X Viewpoint

Picture this: TV wasn’t overflowing with women leads yet. Then came Tennison, breaking barriers as a tough, smart cop battling a sexist system. We kept watching because her struggle felt real, raw, and incredibly relatable. Every episode peeled back layers, revealing the emotional toll of police work. The pacing was impeccable, balancing tense investigations with character depth. The show’s fast edits and striking visuals made it impossible to look away.

Main Characters

- Jane Tennison: A driven detective struggling against prejudice. She’s tough but vulnerable — a rare, groundbreaking female lead.

- Bill Otley: The gruff, seasonal antagonist whose attitude challenges Tennison’s authority. Think of him as the blokey cop with a chip on his shoulder.

- Michael Kernan: Tennison’s often difficult boss, clashing with her unorthodox methods. A classic authority figure in flux.

- Frank Burkin: The dependable investigator who becomes Tennison’s ally, balancing out the chaos.

- Zoe Wanamaker & John Bowe: Early episodes sprinkle in scene-stealing characters adding flavor and narrative depth.

Look and Feel

The series shot in London but feels timeless. Moody interiors, realistic crime scenes, and a deliberate pace create palpable tension. Each episode feels like a mini-movie, combining procedural rigor with character bluffs. You’re not just solving crimes — you’re witnessing Tennison’s soul searching amid chaos.

Story Arcs and Highlights

- Series 1 (1991): Tennison inherits a serial murder case, faces sexist colleagues, and proves her worth.

- Series 2 (1992): Tackles racial tensions in London, testing Tennison’s principles and her reputation.

- Series 3 (1993): Gets more personal as she confronts abuse issues and mental health struggles.

- Series 4–7 (1995–2006): Tennison levels up to DSI, tackling corruption, terrorism, and betrayal in high-stakes cases.

Themes, Tone & Style

Prime Suspect merges procedural action with character-driven storytelling. Scenes shift from heated confrontations to quiet introspection. The show tackles sexism, mental health, and loyalty without sugarcoating. Its raw realism makes it feel authentic and ongoing—still relevant today.

Reception and Awards

The show was hailed critically. Helen Mirren scored three BAFTAs and multiple Emmys. The creator, Lynda La Plante, scooped an Edgar Award and a BAFTA for her sharp writing. Its influence was dramatic enough to inspire a US remake starring Maria Bello, though that didn’t last long. Still, the original remains a cultural touchstone.

Cultural Impact & Legacy

Prime Suspect shook the TV world by creating a flawed, realistic heroine leading the charge. It opened doors for women in crime drama and inspired modern hits like Broadchurch and Luther. Plus, La Plante’s novels and the prequel series, Tennison, keep her story alive. And let’s be honest: we still drop her quotes in social media memes today.

If You Only Watch One Episode…

Watch the pilot. It’s the perfect introduction to Tennison’s world. From her inheriting the serial murder case to facing off with sexist colleagues, it sets the tone. That opening scene with the haunting theme tune and London fog still gives goosebumps. It’s all about grit, determination, and fighting the system — encapsulating what made the series legendary.