5-minute read

Premise

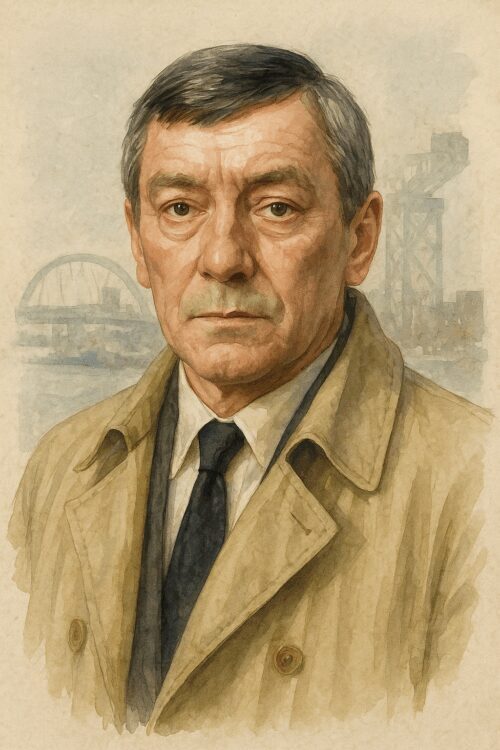

Remember those gritty Glasgow crime dramas you kept watching even when you probably should’ve turned off? That’s Taggart. The series ran from 1983 to 2010, captivating audiences with its raw portrayal of police life and Glasgow’s grimy streets. Once you got hooked on Taggart’s no-nonsense tone, suspenseful pacing, and memorable theme tune, you couldn’t look away. It’s the kind of show you binge on repeat, identifying with the tough characters solving tough cases in a tough city. The show’s relentless energy kept viewers hooked, especially during those intense opening sequences that set the gritty mood instantly.

Characters

- Jim Taggart: Tough, outspoken, with a no-nonsense attitude. As the lead, he’s the moral compass and gruff detective everyone remembers. His voice and attitude became iconic in Scottish crime tales.

- Robbie Ross: Taggart’s steady right-hand man. Calm, dependable, and compassionate, he balances the chaos of Glasgow’s criminal underworld.

- DI Andy Kitson: The by-the-book detective who’s all about following procedure. His cautious approach often clashes with Taggart’s instinctive methods.

- Jackie Reid: Joined in the ‘90s, bringing intelligence and long-term stability. She’s sharp and empathetic, making her a fan favourite.

- Stuart Fraser: Young, ambitious, and eager to prove himself. His evolving style reflects changing police tactics and generational shifts.

Production and Style

Filmed all over Glasgow, the show uses real city streets and grimy interiors to pull viewers into the action. The contrast between gritty outdoor scenes and cold police stations added to the authentic feel. It’s a visual style that screams Glasgow’s soul—tough, real, unforgiving.

Series Structure & Evolution

- 1983–1990: Focused on Taggart and his partner Jim Craig. Balancing gritty crime stories with Scottish city charm.

- 1990–1999: Taggart’s team grows, tackling social issues like gangs and corruption. The show mirrors Glasgow’s changing scene.

- 2000–2010: Following Taggart’s death in 1994, his legacy lives on with new leads like Robbie Ross and Jackie Reid. The cases get more forensic and modern.

Writing, Themes & Tone

‘Taggart’ was never just about solving crimes. It delved into moral complexity, community bonds, and the toll of police work. Transitions between tense crime scenes and personal struggles kept viewers on their toes. Themes of loyalty, justice, and duty were woven into every episode. That’s what made it feel real, not just a police procedural but a reflection of Glasgow’s heartbeat.

Iconic Episodes & Moments

- “Killer” (1983): First episode. Introduces Glasgow’s dark side and Taggart’s relentless pursuit of truth.

- “Under the Hammer” (1990): A chilling serial killer storyline that had viewers glued, revealing the show’s psychological depth.

- “Death Comes Softly” (2003): One of the first stories after Taggart’s death, proving the show could adapt and stay compelling.

Cultural Impact

Everyone knew the iconic line “There’s been a murder” by the late ‘80s. The phrase became part of British pop culture. The theme music and Glasgow backdrop influenced countless police shows. Memes of Taggart’s gruff style pop up on social media today, proof of its lasting resonance. It’s the show every UK crime fan references when discussing classic police dramas.

Legacy

Taggart paved the way for modern UK crime series like ‘Silent Witness’ and ‘Shetland’. Its gritty realism and character-driven stories set a standard. Despite ending in 2010, it remains a beloved staple of British TV history. Long-time fans still debate who was the best detective or moment from the series.

If You Only Watch One Episode

Catch the pilot, “Killer.” It’s the perfect introduction to Taggart’s gritty, no-nonsense style. Plus, it sets the tone for everything that made the series iconic: Glasgow’s dark underbelly, tough cops, and that unforgettable theme tune. Watching it gives you the full Taggart experience in one go. Trust us, you won’t want to miss this essential starting point.